Leon Trotsky, Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev and other left-wing members of the Politburo had always been in favour of the rapid industrialisation of the Soviet Union. Stalin disagreed with this view. He accused them of going against the ideas of Lenin who had declared that it was vitally important to "preserve the alliance between the workers and the peasants." When left-wing members of the Politburo advocated the building of a hydro-electric power station on the River Druiper, Stalin accused them of being 'super industrialisers' and said that it was equivalent to suggesting that a peasant buys a "gramophone instead of a cow." (1)

When Stalin accepted the need for collectivisation he also had to change his mind about industrialisation. His advisers told him that with the modernisation of farming the Soviet Union would require 250,000 tractors. In 1927 they had only 7,000. As well as tractors, there was also a need to develop the oil fields to provide the necessary petrol to drive the machines. Power stations also had to be built to supply the farms with electricity.

However, Stalin suddenly changed policy and made it clear he would use his control over the country to modernize the economy. The first Five Year Plan that was introduced in 1928, concentrated on the development of iron and steel, machine-tools, electric power and transport. Stalin set the workers high targets. He demanded a 111% increase in coal production, 200% increase in iron production and 335% increase in electric power. He justified these demands by claiming that if rapid industrialization did not take place, the Soviet Union would not be able to defend itself against an invasion from capitalist countries in the west. (2)

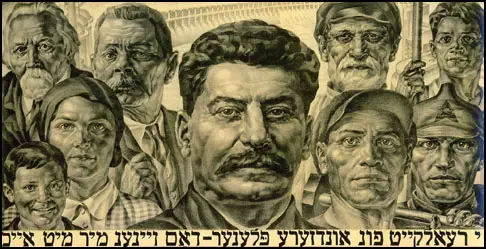

James William Crowl has argued there were political reasons for the introduction of the Five Year Plan: "Stalin With the defeat of Trotsky and the Left Wing in 1927, Stalin apparently began to look for a way to outmaneuver the final power bloc in the Party: the Right Wing led by Bukharin, Rykov and Tomsky. It was not by accident that the economy provided him with the issues he needed to destroy his erstwhile allies. Midway through 1927 the Politburo had initiated an ambitious economic program that included a number of expansive construction projects such as the Turkish-Siberia railroad and the Dnieper dam. Such an undertaking involved a risk since it was to be underwritten largely by the sale of grain, and the grain collection program had become increasingly unreliable during the mid-1920's." (3) Mikhail Cheremnykh, Congratulations (1930)

The first Five-Year Plan did not get off to a successful start in all sectors. For example, the production of pig iron and steel increased by only 600,000 to 800,000 tons in 1929, barely surpassing the 1913-14 level. Only 3,300 tractors were produced in 1929. The output of food processing and light industry rose slowly, but in the crucial area of transportation, the railways worked especially poorly. "In June, 1930, Stalin announced sharp increases in the goals - for pig iron, from 10 million to 17 million tons by the last year of the plan; for tractors, from 55,000 to 170,000; for other agricultural machinery and trucks, an increase of more than 100 per cent." (4)

Every factory had large display boards erected that showed the output of workers. Those that failed to reach the required targets were publicity criticized and humiliated. Some workers could not cope with this pressure and absenteeism increased. This led to even more repressive measures being introduced. Records were kept of workers' lateness, absenteeism and bad workmanship. If the worker's record was poor, he was accused of trying to sabotage the Five Year Plan and if found guilty could be shot or sent to work as forced labour on the Baltic Sea Canal or the Siberian Railway. (5)

One of the most controversial aspects of the Five Year Plan was Stalin's decision to move away from the principle of equal pay. Under the rule of Lenin, for example, the leaders of the Bolshevik Party could not receive more than the wages of a skilled labourer. With the modernization of industry, Stalin argued that it was necessary to pay higher wages to certain workers in order to encourage increased output. His left-wing opponents claimed that this inequality was a betrayal of socialism and would create a new class system in the Soviet Union. Stalin had his way and during the 1930s, the gap between the wages of the labourers and the skilled workers increased. (6)

According to Bertram D. Wolfe, during this period Russia had the most highly concentrated industrial working class in Europe. "In Germany at the turn of the century, only fourteen per cent of the factories had a force of more than five hundred men; in Russia the corresponding figure was thirty-four per cent. Only eight per cent of all German workers worked in factories employing over a thousand working men each. Twenty-four per cent, nearly a quarter, of all Russian industrial workers worked in factories of that size. These giant enterprises forced the new working class into close association. There arose an insatiable hunger for organization, which the huge state machine sought in vain to direct or hold in check." (7)

Joseph Stalin now had a problem of workers wanting to increase their wages. He had a particular problem with unskilled workers who felt they were not being adequately rewarded. Stalin insisted on the need for a highly differentiated scale of material rewards for labour, designed to encourage skill and efficiency and "throughout the thirties, the differentiation of wages and salaries was pushed to extremes, incompatible with the spirit, if not the letter, of Marxism." (8)

Stalin gave instructions that concentration camps should not just be for social rehabilitation of prisoners but also for what they could contribute to the gross domestic product. This included using forced labour for the mining of gold and timber hewing. Stalin ordered Vladimir Menzhinski, the chief of the OGPU, to create a permanent organisational framework that would allow for prisoners to contribute to the success of the Five Year Plan. People sent to these camps included members of outlawed political parties, nationalists and priests. (9)

Robert Service, the author of Stalin: A Biography (2004), has pointed out: "During the First Five Year Plan the USSR underwent drastic change. Ahead lay campaigns to spread collective farms and eliminate kulaks, clerics and private traders. The political system would become harsher. Violence would be pervasive. The Russian Communist Party, OGPU and People's Commissariat would consolidate their power. Remnants of former parties would be eradicated… The Gulag, which was the network of labour camps subject to the People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD), would be expanded and would become an indispensable sector of the Soviet economy… A great influx of people from the villages would take place as factories and mines sought to fill their labour forces. Literacy schemes would be given huge state funding… Enthusiasm for the demise of political, social and cultural compromise would be cultivated. Marxism-Leninism would be intensively propagated. The change would be the work of Stalin and his associates in the Kremlin. Theirs would be the credit and theirs the blame." (10) Adolf Strakhov, "We are the Realisation of the Plan (1933)

Eugene Lyons was an American journalist who was fairly sympathetic to the Soviet government. On 22nd November, 1930, Stalin selected him to be the first western journalist to be granted an interview. Lyons claimed that: "One cannot live in the shadow of Stalin's legend without coming under its spell. My pulse, I am sure, was high. No sooner, however, had I stepped across the threshold than diffidence and nervousness fell away. Stalin met me at the door and shook hands, smiling. There was a certain shyness in his smile and the handshake was not perfunctory. He was remarkably unlike the scowling, self-important dictator of popular imagination. His every gesture was a rebuke to the thousand little bureaucrats who had inflicted their puny greatness upon me in these Russian years. At such close range, there was not a trace of the Napoleonic quality one sees in his self-conscious camera or oil portraits. The shaggy mustache, framing a sensual mouth and a smile nearly as full of teeth as Teddy Roosevelt's, gave his swarthy face a friendly, almost benignant look." (11)

Walter Duranty was furious when he heard that Stalin had granted Lyons this interview. He protested to the Soviet Press office that as the longest-serving Western correspondent in the country it was unfair not to give him an interview as well. A week after the interview Duranty was also granted an interview. Stalin told him that after the Russian Revolution the capitalist countries could have crushed the Bolsheviks: "But they waited too long. It is now too late." Stalin commented that the United States had no choice but to watch "socialism grow". Duranty argued that unlike Leon Trotsky Stalin was not gifted with any great intelligence, but "he had nevertheless outmaneuvered this brilliant member of the intelligentsia". He added: "Stalin has created a great Frankenstein monster, of which. he has become an integral part, made of comparatively insignificant and mediocre individuals, but whose mass desires, aims, and appetites have an enormous and irresistible power. I hope it is not true, and I devoutly hope so, but it haunts me unpleasantly. And perhaps haunts Stalin." (12)

Some people complained that the Soviet Union was being industrialized too fast. Isaac Deutscher quoted Stalin as saying: "No comrades. the pace must not be slackened! On the contrary, we must quicken it as much as is within our powers and possibilities. To slacken the pace would mean to lag behind; and those who lag behind are beaten. The history of old Russia. was that she was ceaselessly beaten for her backwardness. She was beaten by the Mongol Khans, she was beaten by Turkish Beys, she was beaten by Swedish feudal lords, she was beaten by Polish-Lithuanian Pans, she was beaten by Anglo-French capitalists, she was beaten by Japanese barons, she was beaten by all - for her backwardness. We are fifty or a hundred years behind the advanced countries. we must make good this lag in years. Either we do it or they crush us." (13)

In 1932 Walter Duranty won the Pultzer Prize for his reporting of the Five Year Plan. In his acceptance speech he argued: "I went to the Baltic states viciously anti-Bolshevik. From the French standpoint the Bolsheviks had betrayed the allies to Germany, repudiated the debts, nationalized women and were enemies of the human race. I discovered that the Bolsheviks were sincere enthusiasts, trying to regenerate a people that had been shockingly misgoverned, and I decided to try to give them their fair break. I still believe they are doing the best for the Russian masses and I believe in Bolshevism - for Russia - but more and more I am convinced it is unsuitable for the United States and Western Europe. It won't spread westward unless a new war wrecks the established system." (14)

Some people argued that Duranty had been involved in a cover-up concerning the impact of the economic changes that were taking place in the Soviet Union. An official at the British Embassy reported: "A record of over-staffing, overplanning and complete incompetence at the centre; of human misery, starvation, death and disease among the peasantry. the only creatures who have any life at all in the districts visited are boars, pigs and other swine. Men, women, and children, horses and other workers are left to die in order that the Five Year Plan shall at least succeed on paper." (15)

By John Simkin (john@spartacus-educational.com) © September 1997 (updated January 2020).No comrades. the pace must not be slackened! On the contrary, we must quicken it as much as is within our powers and possibilities. To slacken the pace would mean to lag behind; and those who lag behind are beaten. The history of old Russia. was that she was ceaselessly beaten for her backwardness. She was beaten by the Mongol Khans, she was beaten by Turkish Beys, she was beaten by Swedish feudal lords, she was beaten by Polish-Lithuanian Pans, she was beaten by Anglo-French capitalists, she was beaten by Japanese barons, she was beaten by all - for her backwardness. We are fifty or a hundred years behind the advanced countries. we must make good this lag in years. Either we do it or they crush us.

A record of over-staffing, overplanning and complete incompetence at the centre; of human misery, starvation, death and disease among the peasantry. the only creatures who have any life at all in the districts visited are boars, pigs and other swine. Men, women, and children, horses and other workers are left to die in order that the Five Year Plan shall at least succeed on paper.

The period of the Five Year Plan has been christened Russia's "Iron Age" by the best-informed and least sensational of my American colleagues in Moscow, William Henry Chamberlin. I can think of no more apt description. Iron symbolizes industrial construction and mechanization. Iron symbolizes no less the ruthlessness of the process, the bayonets, prison bars, rigid discipline and unstinting force, the unyielding and unfeeling determination of those who directed the period. Russia was transformed into a crucible in which men and metals were melted down and reshaped in a cruel heat, with small regard for the human slag.

It was a period that unrolled tumultuously, in a tempest of brutality. The Five Year Plan was publicized inside and outside Russia as no other economic project in modern history. Which makes it the more extraordinary that its birth was unknown and unnoticed.

The Plan sneaked up on the world so silently that its advent was not discovered for some months. On the momentous October first of 1928, the initial day of the Five Year Plan, we read the papers, fretted over the lack of news and played bridge or poker as though nothing exceptional was occurring. It was the beginning of a new fiscal year, precisely like the October firsts preceding it. The "control figures" or plan for the ensuing twelve months were rather more ambitious, with new emphasis on socialization of farming through state-owned "grain factories" and voluntary collectives of small holdings. But they were not sufficiently different from other years to arrest the attention of competent observers.

The fact is that the Kremlin itself was far from certain that a new era had been launched. It had not yet charted a course. Or rather, it had charted alternative courses and hesitated in which direction to move. Not until Stalin and his closest associates see fit to reveal what happened in the crucial months of that autumn will we know how close the Soviet regime came to choosing a course which would have altered the whole history of Russia and therefore of the present world.

There was nothing in the figures for the fiscal year of 1929 that committed the ruling Party to a Five Year Plan of the scope eventually announced. But a feeling of tense expectancy now stretched the country's nerves taut. A sharp turn of the wheel to one side or the other was inevitable, and the population squared for the shock. Economic difficulties were piling up dangerously and the Kremlin could not steer a middle course much longer. Food lines were growing longer and more restive. The producers of food had tested their strength and tasted a measure of victory; they rebelled more boldly against feeding the urban population and the armies for rubles which could buy nothing. Millions of grumbling mouths had to be either filled with food or shut by force.

A partial crop failure in southern Russia aggravated the situation. Grain collections were not going well and, as always happened under these circumstances, the collectors began to resort to strong-arm tactics. Arson and assassination flared up once more in the villages, and Red troops were said to be "pacifying" the most unruly districts with lead. Schools, clubs, government buildings, and other institutions typifying the Soviet power were burned down in dozens of places. The published details of the peasant revenge were sufficiently harrowing, and what the press reported, we all assumed, was no more than a fraction of the picture. Death penalties, with and without trials, were the government's automatic answer. But they did not suffice. Something decisive had to be done that would either placate the peasants or end their insubordination.

With the defeat of Trotsky and the Left Wing in 1927, Stalin apparently began to look for a way to outmaneuver the final power bloc in the Party: the Right Wing led by Bukharin, Rykov and Tomsky. It was not by accident that the economy provided him with the issues he needed to destroy his erstwhile allies. Midway through 1927 the Politburo had initiated an ambitious economic program that included a number of expansive construction projects such as the Turkish-Siberia railroad and the Dnieper dam. Such an undertaking involved a risk since it was to be underwritten largely by the sale of grain, and the grain collection program had become increasingly unreliable during the mid-1920's. The yearly crises stemmed in part from insufficient supplies of consumer goods, but they were even more the result of the low price the government offered for grain. As a result of that price, peasants turned over to the state only the grain they were required to deliver through the procurement quotas, and they sold the rest through Nepmen on the private market where the price was substantially higher. Yet, in order to raise the additional revenue needed for the industrial program in 1927, the state dropped its price for grain still lower and cracked down on the private market in an effort to force the peasants to sell their grain to the state at the lower price. The peasants responded, however, by feeding their grain to their cattle, turning it into alcohol, or hoarding it in expectation of higher prices. By late 1927, grain collections fell off more sharply than in earlier years, and the regime faced a crisis.

Signs of disagreement over the response to the crisis appeared as early as October 1927. Stalin and his henchmen sounded the need for anti-kulak measures, while Bukharin and his allies worried aloud about the lagging collections but insisted on the need for caution in finding a solution. Unity was maintained at the Fifteenth Party Congress in December, however, as even the Politburo rightists agreed that action was needed to convince the peasants to relinquish their supplies. Thus the Congress that vanquished Trotsky fairly bristled with leftist declarations.

A heavier, graduated procurement tax was issued that hit directly at the kulaks and promised to bring the state additional grain. In addition, a land act rescinded the right to hire labor and lease land that had been granted to peasants in 1925 and 1926, and kulaks were deprived of their voting rights in order to curtail their power in the village soviets. The Congress encouraged collectivization as well, although it stressed that it should be a gradual and voluntary process. Because of such measures, the Fifteenth Congress is often cited as marking the end of the N.E.P, era.

In the weeks following the Congress, Bukharin, Rykov and Tomsky apparently again supported Stalin in the attempt to compel the peasants to turn over their grain. Stalin was given control of the effort, and he singled out West Siberia for his personal attention since the harvest there had been excellent and the peasants were believed to be holding back substantial grain supplies. Though the Politburo still issued reassuring reports claiming that the Party had not broken with past agricultural policy, the Soviet press wrote about the grain "front" as if a military campaign had begun. Violence was widespread as officials tried to ferret out the grain, and Alec Nove claims that for some time thereafter such arbitrary and violent grain seizures were referred to as the "Urals-Siberian" method, after Stalin's tactics of early 1928. Though grain collections lagged and even the new procurement quotas fell short in January and February, by March the grain seizures were successfully at last in bringing the state the needed grain.

Until February and March of 1928, when the confrontation with the peasants reached a highpoint, it appears that Bukharin reluctantly agreed that temporary measures against grain-hoarding were necessary. The violence of the campaign was repulsive to the Politburo Right, however, and jolted it into an awareness of the deep division that had been developing in the Party since the fall of 1927. As a result, the two Politburo factions clashed repeatedly in the late winter, and Stalin found it necessary to publicly repudiate the "Urals-Siberian" methods at times over the next few months. Nevertheless Stalin had apparently committed himself to a radical economic stance by the late winter of 1927-1928, if only as a means of striking at his foes, and the power struggle had begun again in earnest.

Was the first Five Year Plan a "success"? For whom and for what? Certainly not for the socialist dream, which had been emptied of human meaning in the process, reduced to a mechanical formula of the state as a super-trust and the population as its helpless serfs. Certainly not for the individual worker, whose trade union had been absorbed by the state-employer, who was terrorized by medieval decrees, who had lost even the illusion of a share in regulating his own life. Certainly not for the revolutionary movement of the world, which was splintered, harassed by the growing strength of fascism, weaker and less hopeful than at the launching of the Plan. Certainly not for the human spirit, mired and outraged by sadistic cruelties on a scale new in modern history, shamed by meekness and sycophancy and systematized hypocrisy.

If industrialization were an end in itself, unrelated to larger human ends, the U.S.S.R. had an astounding amount of physical property to show for its sacrifices. Chimneys had begun to dominate horizons once notable for their church domes. Scores of mammoth new enterprises were erected. A quarter of a million prisoners -a larger number of slaves than the Pharaohs mobilized to build their pyramids, than Peter the Great mobilized to build his new capital-hacked a canal between the White and the Baltic Seas; a hundred thousand survivors of this "success" were digging another canal just outside Moscow as the second Plan got under way. The country possessed 3 blast furnaces and 63 open hearth furnaces that had not existed in 1928, a network of power stations with a capacity four times greater than pre-war Russia had, twice as many oil pipe lines as in 1928. Hundreds of machines and tools formerly imported or unknown in Russia were being manufactured at home and large sections of mining were mechanized for the first time. The foundations were laid for a new industrial empire in the Urals and eastern Siberia, the impregnable heart of the country. Two-thirds of the peasantry and four-fifths of the plowed land were "socialized"-that is, owned and managed by the state-employer as it owned and managed factories and workers. The defensive ability of the country, in a military sense, had been vastly increased, with new mechanical bases for its war industries.

Measured merely for bulk, the Plan achieved much, though it fell far short of the original goals. On the qualitative side, the picture is much less impressive. Here, we find reflected the low caliber of the human material through which the Plan was necessarily translated from paper to life. Overhead costs were greater all along the line than expected.